Before reading this article I recommend that you read another article I’ve wrote on the subject of the drawbacks of training volume research. It goes into detail about why it can be difficult to make fair comparisons of training volume due to the presence of many confounding variables. I’ll reference it in this article.

What is Training Volume?

Training volume is the dose of the training stimulus that you subject your body to. This dose will determine the training effect that you get, both in terms of strength/muscle growth stimulated and the fatigue generated

A common definition used for training volume is actually

Tonnage = weight x reps x sets.

In the context of strength and hypertrophy this isn’t very useful. We don’t care about volume in the technical sense. We care about how effective that volume is for stimulating strength and muscle growth. Not all volume is equal. There are many confounding variables that influence what effect a given amount of training volume gives you.

These confounding variables including:

- Proximity to failure (RPE)

- Exercise selection

- Exercise execution

- Exercise order

- Rep ranges

- Rest periods

- Training frequency

- Muscle overlap

These are the main factors that determine what effect a dose of training volume gives you. Again I go into these in more detail in the article linked above.

For example it’s not uncommon to be able to leg press twice as much weight as you squat (depending on the machine).

To get equivalent volumes with twice the weight and the same reps you would need half the sets.

4x8x150kg Squat = 4800kg

2x8x300kg leg press = 4800kg

You can lift more weight but that doesn’t make your volume better for hypertrophy

2 sets on the leg press can be significantly different to 4 sets on the squat in terms training effect. However the volume would technically be the same for both.

Using this example we can see how confounding variables such as exercise selection can mess up comparisons of training volume when using the simple technical definition of training volume.

Using Hard Sets to Track Volume

The most common way of simplifying this is tracking hard sets (5+ rep range). This takes out the massive variable of rep ranges. All rep ranges within about 5-30 stimulate hypertrophy just as well as each other if taken close enough to failure.

Reps need to be above a certain threshold. Below around 5 reps the muscle is simply not under tension for long enough to maximally stimulate hypertrophy. It seems that reps that are too high have such minimal tension that the time under tension can’t fully compensate. This is where the 5-30 rep range comes from

Other factors affect this rep number (such as tempo and range of motion). Squats with a controlled negative and long pause for sets of 4 to failure may actually stimulate hypertrophy better than sets of 5 to failure where you’re just getting through the reps as quickly as possible. 5 reps is just a pretty good average across all exercises.

For strength sets there isn’t a minimum rep range, it’s purely a function of how heavy you’re going relative to your max (%1RM).

Most people will be looking to build muscle as well. These don’t have to be a focus at the same time. If you’re like me and you want to train both at the same time check out this article explaining exactly how to do that.

How Adjusting Each Variable Affects Set Count and Effective Volume

Proximity to Failure (RPE)

I’ve written an extremely in depth article on RPE. To simplify this as much as possible the higher the RPE the higher the stimulus and also the fatigue generated. Higher RPEs lead to larger effective volumes.

Exercise Selection

This is largely individual dependant however there are some similarities across almost everyone. For example a paused high bar squat will tend to be more stimulative or at the very least just as stimulative for the quads as a low bar squat.

You also won’t be able to lift as heavy on a paused high bar as you can on a low bar squat. Even if hard sets are the same the effective volume for the quads will probably be higher for paused high bar squats. Paused high bar squats also lead to less systemic fatigue and more sets of them can be performed before overreaching. Therefore in the majority of cases they are better exercise for quad hypertrophy.

Exercise Execution

How you execute a lift will affect how effective the volume is. When you squat you can just try to get through the reps or really focusi on positioning throughout.

If you just try to get as many reps as possible at any cost you might end up leaning forward and rounding your back to use more of your glutes and lower back. If you try to stay fairly upright with a neutral spine and fight to keep your knees forward out of the hole you may lose a few reps reps but achieve a better quad stimulus. In this latter case even with the same number of hard sets the effective volume for your quads is greater.

This includes range of motion as well, a powerlifter with an extreme arch and a very short range of motion will get less of a stimulus per set and will be able to tolerate more volume than a more usual flat back style of benching.

Exercise Order

Again carrying on with this squat example, we can change the order of exercises to maximise the effective volume of an exercise. Lets say your quads are a strong point and your core, back and glutes are relatively weak. Squatting when fresh can put your quads at a pretty low RPE as your core, back or glutes could be the limiting factor. This is poor for hypertrophy. You can do leg extensions later to take the quads near failure but we can sequence this better to take them to failure in both.

If we did leg extensions first we could take them to failure and fatigue the quads enough so that when we squat the quads are taken to failure when squatting too. The number of hard sets is the same in both cases, the effective volume in the latter case will be greater.

This is not ideal for strength as you will probably see a small drop off in weight lifted but it can be useful for hypertrophy.

Rep Range

Using hard sets (discussed above) takes care of this.

Rest Periods

Rest periods that are so short that you aren’t recovered won’t allow you to stimulate the muscles involved as well. This leads to lower effective volumes. We even have research to support this.

Training Frequency

There seems to be a sweet spot that varies per muscle group which determines what training frequency leads to the highest effective volumes.

Training a muscle group extremely frequently will mean you will have to warm up more often. You also won’t be able to do many sets per session. Warming up is mostly junk volume (doesn’t contribute to stimulus but adds fatigue) and there is the possibility that more advanced lifters need a certain threshold of stimulus per session to stimulate any growth. When the frequency is extremely high this may lead to spreading yourself so thin that this isn’t achieved.

Conversely if your frequency is too low you have to squeeze a lot of sets into fewer sessions. This may mean the later sets are lower quality due to fatigue leading to less effective volume.

Muscle Overlap

Different exercises that use the same muscle groups will stimulate different regions of muscle to different extents. Compound lifts may stimulate multiple muscle groups but they won’t stimulate every muscle group involved maximally.

If you’re counting a compound movement as a full set for all muscle groups involved the actual effective volume will be lower in many cases. This is why we have a study that shows muscle growth increased up to 45 sets per week. In practice I don’t know anyone who could even tolerate that if we’re talking about isolation movements close to failure, let alone benefit from it.

Does a high bar squat count as a full set for quads and glutes? What if your sticking point is right out of the hole and after a hard set your quads are fatigued but your glutes feel like they’ve barely been worked? Is this still a full set for both?

This is one reason why I believe that considering movement patterns in addition to muscle groups is better than considering just muscle groups.

Movement Patterns vs Muscle Groups

I believe using movement patterns instead of just muscle groups to count training volume to be superior. There are several movement patterns that are almost always a constant in someones training program.

Exercises that use similar movement patterns are more similar than exercises just that use the same muscle groups. When it comes to strength there will tend to be more compound movements that use multiple muscles as prime movers. Considering just muscle groups is overly simplistic. For a more in depth look at the differences between training for strength and hypertrophy and how to combine them effectively check this article out.

The list of movement patterns I tend to use include:

Vertical pulls

Horizontal pulls

Machine/free weight squat/leg press

Hip hinge (including deadlifts)

Presses can be subdivided into:

flat/decline/dips

incline

overhead

Then each body part can have a tally for “isolation” type lifts, such as biceps,triceps, chest, traps, side delts, rear delts, hamstring, quads, glutes, abs.

This isn’t an exhaustive list but will cover every exercise that most people have in their program.

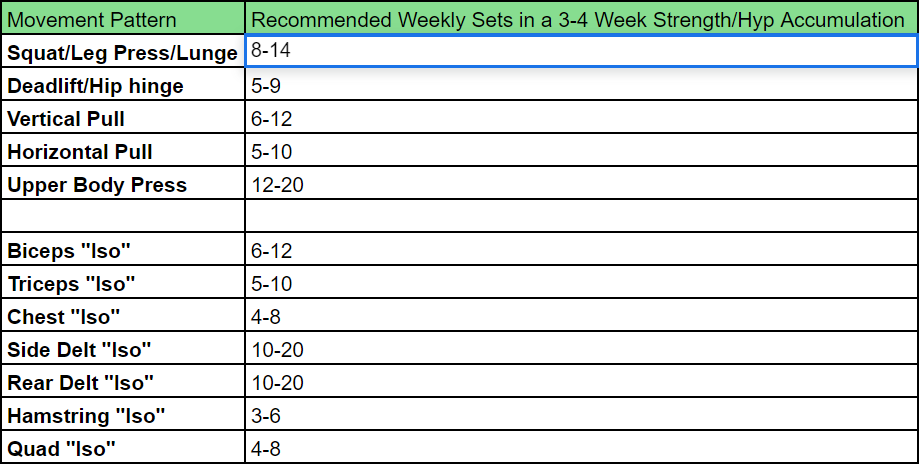

Most of the recommendations out there are from the perspective of counting sets on a per muscle basis. I haven’t seen this elsewhere so I’ll give rough recommendations that you can uses as a starting point if you’re not used to tracking volume like this.

This is based on working with a variety of clients whose goal is both strength and hypertrophy. Pure strength based training will have slightly lower set numbers and pure hypertrophy training will have slightly higher set numbers.

Counting sets of chest presses and flys is more useful than just counting sets of “chest” for example. This is something powerlifters have sort of been doing for a while.

That is counting sets of bench, squat and deadlift along with accessories. This can be applied well to general strength and hypertrophy training.

The Main Reason Why Considering Movement Patterns is Better

It decreases the effect of the confounding variable of muscle overlap. What even is a set of back, really? There’s so many different muscles and one movement pattern can’t effectively target them all.

There will be some overlap but horizontal pulls will bias different muscles than vertical pulls. What about deadlifts? They use your back as well, the training effect and fatigue accumulation is vastly different from a lat pulldown though. Even if you don’t count deadlifts as a set of back, increasing your deadlift volume will affect how much volume of other back movements you can do.

Is a bench press a set for chest, front delts or triceps?

Does it count as a full set for all 3? probably not. Maybe it’s a full set for chest, 0.6 sets for triceps and 0.4 sets for front delts for example. We could round to 1, 0.5 and 0.5. Is this a reasonable way to count it, maybe.

I would prefer to just keep a tally of flat presses so this doesn’t become an issue. If/when you add a different exercise/sub in a new one you can determine how this changes the stimulus and fatigue by how that exercise differs to the existing baseline. Yes you could do that with just muscle groups but the variability is much larger and that can lead to significant errors.

For example let’s say you were originally doing just bench presses for your chest and you were doing 10 sets a week. If you swapped 5 of these sets for weighted dips and you were counting dips as a full set for your chest this would be seen as the same amount of sets for your chest but the stimulus has probably gone down. Because for most people a set of dips will stimulate their chest less than a set of bench press.

If you were only counting dips as half a set for chest then sure you’re accounting for the decreased stimulus, but maybe the magnitude of decrease is a bit off. There would be less error if you just compared similar movement patterns.

A barbell bench and dumbell bench are pretty similar, flat presses and weighted dips are less similar, flies and any kind of press are very different due to muscle overlap from compound movements. Using movement patterns instead of muscle groups will reduce the error here.

Set Recommendations per Movement Pattern

There is quite a big range here and there has to be when giving broad recommendations. The effects of individual genetics, recovery factors, level of advancement and all the factors mentioned above will mean what is “optimal” will vary greatly between people.

All of my clients past the novice stage fall somewhere within this range. I recommend starting at the lower end of each recommendation and working up. Chances are that you won’t be able to tolerate the higher end in every single category. I know I can’t.

When I have had clients who can tolerate more they weren’t very advanced and they weren’t training quite as hard as they should be. The vast majority of people won’t be at the higher end of the ranges in every category.

There will be outliers who fall above/below this range but this won’t be most people if they’re training and recovering properly. Outliers who fall below this range tend to be extremely advanced and/or take every working set to failure. Outliers above this range tend to train too far away from failure, essentially doing a lot of junk volume.

The isolation exercises all tend to be the same movement pattern or extremely similar movement patterns that have very similar effect on fatigue and stimulus.

Other movement patterns can be used, occasionally glute, trap or ab exercises are used. This covers every exercise used by lifters training for strength and hypertrophy in the majority of situations. If you want to add some of that stuff in just lower the sets in the other categories a bit.

I always split pressing up, I have left it as one big category in the table as I know many people like to include an overhead press variation in their training. I rarely program it as I believe it to be overrated (this doesn’t mean bad/useless) unless you specifically want a stronger overhead press.

The more you split up your volume between the different pressing movement patterns the more you sets you can benefit from doing.

For example you can tolerate more sets doing an incline press, dip/flat press and ohp variation than if you just did flat variations.

Dealing with the Remaining Confounding Variables

We’ve gotten rid of rep ranges and diminished the effect of muscle overlap and exercise selection but we still have all the others to contend with. The good thing is that these are two of the most important considerations. If we still have all of these confounding variables how do we track sets?

I think of this a similar way to tracking steps. Tracking steps will have some error associated with it. i.e 10,000 steps tracked may actually range between 9500 and 10500, that isn’t a big deal as the error is consistent.

It doesn’t matter if it’s inaccurate as long as its consistently inaccurate.

The inaccuracies from the other variables aren’t as important as they will have a smaller overall effect on “effective volume” or they will be largely consistent from mesocycle to mesocycle. RPE adjustments will be very similar from meso to meso so we don’t have to factor in how fluctuations in RPE affect the stimulus and fatigue.

The remaining minor inaccuracies will largely be smoothed out by considering how each change you make will affect effective volume. Unless you make drastic changes to your training style you can still use past experience to dose training volume. Drastic changes will be very rare, if they happen one mesocycle should be enough to establish a new baseline.

You should only compare the number of sets per movement pattern/muscle group to your previous set counts not to other peoples values.

If someone else is training in a way where they’re consistently training at lower RPEs and have poor exercise execution they’ll be able to do more sets. This is before even taking into account individual factors such as genetics and level of advancement. This is one of the reasons why training volume research is extremely limited when it comes to informing you about how many sets you should do for optimal progress.

Interested in coaching to take your progress to the next level?