Why Quantify Training Volume?

Why does training volume matter?

The dose of training volume has a significant effect on the hypertrophy (muscle growth) stimulus and the fatigue generated from that training. It’s useful to be able to quantify training volume so that we can see what affect altering training volume has on results.

Training volume is commonly measured in hard sets executed per bodypart. Usually a hard set is considered a set done in the 5-30 rep range taken 0-4 reps from failure (RPE 6-10).

Already see some issues with that definition? We’ll get to it later.

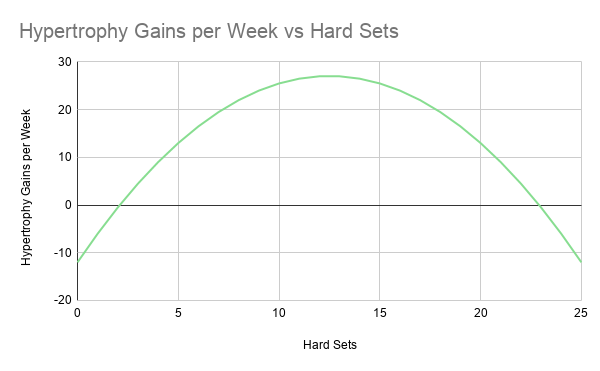

Based on the current research it appears that there is a very low threshold of training volume necessary for strength. However the relationship between training volume and hypertrophy seems to be that of a U shaped curve.

There is a low threshold (lower than most think) of volume needed to maintain any current muscle gains, below which you will atrophy (lose gains).

Above maintenance volume an increase in training volume will lead to more gains, up to a point.

After this point they plateau and then further increases in volume actually decrease gains in hypertrophy.

This can be taken so far that you get to a point where further increases in volume actually lead to negative gains (atrophy).

This graph is roughly shows what this U shaped curve will look like. Don’t read too much into the specific numbers as they’re arbitrary and just there to illustrate a general point. The curve won’t look symmetrical either.

The goal of most training volume research is to figure out the specific properties of this curve for the average lifter.

The Confounding Variables when Quantifying Training Volume

A common technical definition of training volume is actually that of volume load, weight x reps x sets.

We’re not trying to track volume just to see how much work our muscles have done. The purpose of tracking it is to see how effective this volume is for stimulating hypertrophy and/or strength.

In the context of strength and hypertrophy this technical definition isn’t useful. There are many variables that influence how stimulating and fatiguing training volume is.

These variables include

Proximity to failure (RPE)

Higher RPEs (closer proximities to failure) will increase the stimulus and also fatigue generated from a given amount of volume. Higher RPEs will therefore lead to higher “effective volume”

Rep range

Rep range and RPE are linked just like many of the other variables. To get the same volume with a lower rep range (heavier weights) you’ll need to do more hard sets.

The rep range that stimulates hypertrophy maximally if taken to a sufficient proximity to failure (high enough RPE) is quite broad. This range is considered to be around 5-30 reps per set.

This isn’t to say rep ranges of say 50 don’t stimulate any, they’re just less efficient and need more hard sets to achieve the same stimulus.

The fatigue lower rep ranges generate also limits how much volume you can do with that weight. Taking 72% of your max for a 5*8 is very doable, it can be done with normal rest periods and can be repeated relatively frequently. Now imagine doing 90% of your max for 32 singles.

In both cases the volume is exactly the same. However the singles would take an ungodly amount of time. If you even managed to complete it (unlikely) without getting injured the fatigue generated would be so high that you’d need some sort of deload after 1 workout like that.

Extremely high or low reps can both influence the effective volume you get. Hard sets remedy this somewhat but can still skew the results.

Exercise selection

Some exercises will be more stimulating to a given individual than others. A lifter may get better chest stimulation from flat dumbell bench press volume than flat barbell bench press volume.

Exercise execution

How you execute an exercise can have a massive effect on how different muscles get targeted, how much “effective volume” you get and how much fatigue is generated.

Doing high bar squats while limiting the amount of forward lean you allow yourself to utilise will generate a higher stimulus for the quads for any given amount of volume. Allowing your knees to shoot back, leaning over more and turning it into a squat good morning hybrid will lead to less quad stimulus and greater systemic fatigue.

Exercise order

Pre fatiguing a muscle with an isolation exercise before a compound exercise can allow you to get the same amount of stimulation for that given muscle while using lighter loads on the compound.

For example doing leg curls before RDLs can allow you to stimulate the hamstrings just as well and will also force you to use lighter weights on the RDL. This means you’ll be training with less overall less volume and generating less systemic fatigue. Due to reduced fatigue levels you can allocate more volume and recovery resources elsewhere.

Training frequency

Training a muscle more frequently can allow you to get in a greater amount of “effective volume”. If you normally do 10 sets of quads once a week, adding 4-6 more in that workout may barely lead to an increase in hypertrophy. You’ll be very fatigued by the time you start those extra sets.

Doing 7-8 sets twice a week will allow you to get more “effective volume” in than doing 14-16 in one workout.

Connective tissue recovery should also be taken into account. You can train a movement pattern so frequently that you irritate the connective tissue associated with that movement pattern. This limits how many sets you do even though your muscles can handle more.

Rest periods

You can take rest periods that are so short that you’re not close to recovered before your next set. When hard sets are equated longer rest periods still seem to be superior to shorter rest periods for hypertrophy.

Muscle overlap between exercises

It’s difficult to determine how you count the sets per body part for a multi joint compound movement.

A set of curls is a set for biceps as the biceps is the only prime mover. What about a chinup? It’s clearly not 0 sets as biceps growth can occur from using chinups as the only biceps movement.

Is it 35%, 50%, 72% of a set? I don’t think we can really say. In many cases a useful way to not overcomplicate things is to count it as half a set, though this is certainly not accurate in many cases.

Why Hard Sets is More Useful Than Volume Load

Using hard sets doesn’t get rid of many of these factors but it’s a lot better than just tracking the total kg lifted (volume load)

I also don’t think that hard sets not being able to fully take into account these above variables is a huge issue.

These factors should just be considered when changes are made to a baseline program.

Let’s take an example where you decide to alter average RPE and exercise selection. Using your understanding of how the changes affect your stimulus and fatigue levels you can decide whether it makes sense to slightly increase, decrease or keep the set numbers the same.

If you changed movements from flat dumbell press to flat barbell press, you may be changing to a more stimulating exercise for your chest.

You may also lower the average RPE in your new mesocycle, this change would lead to less chest stimulation. These 2 factors may cancel each other out.

Just considering these 2 factors it may make sense to leave the training volume where it is as the stimulus is relatively unchanged. If there are other changes coming from the other variables above you may reach a different conclusion depending on how things are weighted.

The Specific Issue With Training Volume Studys

People don’t realise that they’re not training hard, no really. They don’t realise how far away from failure they’re actually training.

I think this is pretty obvious even without research, just observe how most people train in any gym. We have research that supports this as well. This study examined if people could actually predict how many reps they could get with a given load. Are they actually training as hard as they think they are?

To quickly summarise. 141 lifters with varying levels of resistance training experience were observed in the study. They were instructed to train using one set to concentric failure (RPE 10) using exercises and loads they’d normally train with.

Before each working set they were asked to predict how many reps they’d be able to get if they went to complete concentric muscular failure (i.e. they’d try another rep and could not complete it).

On average the lifters predictions were 3 reps BELOW how many they got, i.e they thought they’d get 10 reps and ended up getting 13.

On average people in this study thought their RPE 7 was RPE 10. This gap decreases slightly as training experience increases but even very experienced lifters do this, just to a lesser extent.

This was the AVERAGE, some people were consistently training way more than 3 reps below where they thought they were!

I’m willing to bet that some of the lifters still gave up prematurely and they had even more reps in the tank.

Most training programs I write prescribe compound movements to be taken 1-3 reps from failure (RPE 7-9).

I can give someone a program with sets of RPE 7 in. Without an impartial experienced eye the average person would be training 6 reps from failure, essentially running the program in an almost useless way.

This is one of the reasons why I believe coaching to be far more valuable than just giving someone a program. It’s rare for someone to be able to judge RPE accurately. Even experienced lifters benefit from accountability in keeping their RPEs honest.

This is very relevant to training studies in particular as participants aren’t as experienced. Do you know any high level lifters who would intentionally let their training be subverted so they can participate in a study like this for the good of science? I’m struggling to come up with anyone.

There’s also not as many high level lifters to go around so this leads to the majority of studies using beginners and early level intermediates as the primary subjects. Often a trained lifter in a study has around a 1x bw bench or a 1.5x bw squat which are all usually achievable in the first 9-18 months of lifting.

This shows why research about training volume is limited in usefulness.

Firstly they’re not actually training close to as hard as they’re meant to be. The effectiveness of training volume is in large part determined by proximity to failure (RPE).

There’s a massive difference in hypertrophy response from:

Doing 2 sets of 8 with 200kg @ RPE 8 and 9.

Doing 8 sets of 2 with 200kg with the hardest set being below RPE 5, at best this is technique work/a kind of deload.

Secondly there is a good reason to believe that as you get more advanced you need to train closer to failure to achieve decent results. The findings from novice and early intermediate lifters will not necessarily apply very well to more advanced lifters.

Now compound these 2 factors and the real world application of a lot of research on training volume can be questionable at best.

Even the “expert” trainees (top 42/141) in this study who had the most experience underpredicted how many reps they could get on every single exercise. On more difficult “grindy” exercises like the leg press even “expert” lifters were 1.5-2 reps off.

The discussion at the start of this podcast (time stamped) with Lyle Mcdonald also shows why it’s hard to believe the participants in studies are training as hard as they think they are.

Who is doing 5 sets of squat/leg press to failure with 90s rest? Or 8 sets of 10 to failure with 60s rest?!?

Sure, some rare individual can manage it. The vast majority of participants in any given study are not coming close.

This is another reason why it’s hard to believe that in research on training to failure they’re actually training to failure. These numbers seem more reasonable if we are talking about leaving 2-4 reps in the tank (RPE 6-8) which I expect is closer to what is actually happening.

We tend to get inflated number of how many sets are necessary for optimal hypertrophy. This is because many studys tend to assume people are training to actual failure when they’re not.

These studies also don’t tend to take into account muscle overlap very well. Often a set for a compound movement such as the bench press would count as a full set for triceps.

A set of bench press will definitely stimulate triceps muscle growth but it’s clear that in the vast majority of cases it won’t be as stimulating as a set of a more targeted triceps movement like a triceps extension. It’s probably closer to half a set for triceps however many studies count it as a full set. This is another factor playing leading to why we see such inflated numbers for sets per body part required for maximum hypertrophy.

Everyone seems to have a different idea of what failure actually is. The effectiveness of training volume heavily depends on how close you are to failure. Due to the factors above research on training volume isn’t very useful for more advanced lifters, the group that probably needs it the most.

Interested in coaching to take your progress to the next level?